Five Pillars of a Lost Profits Analysis Pt. 1

Pillar One: Lost Revenues

Introduction

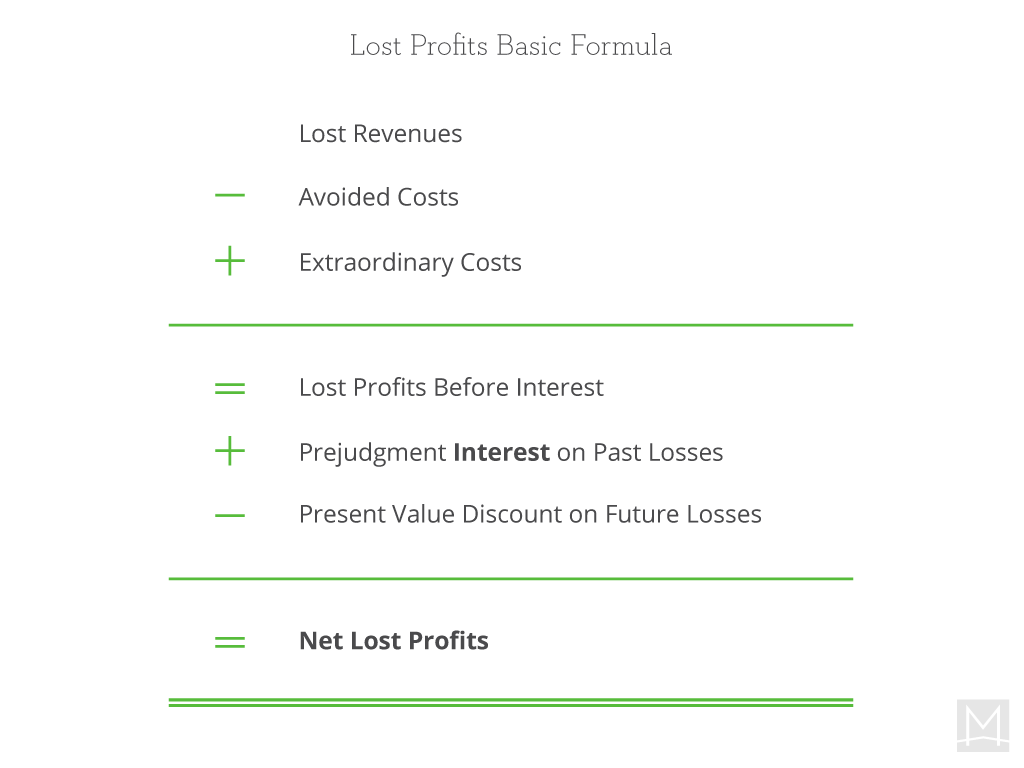

A damage expert who conducts a lost profits analysis attempts to answer the following question: What amount of profits would the plaintiff have earned, but for the actions of the defendant? To completely answer this question, a damage expert must evaluate at least five pillars of a lost profits analysis using reliable methodologies, analytical processes, and underlying data. These five pillars are: lost revenues, avoided costs, extraordinary costs, the damage period and the time value of money. This first article of a five-part series will discuss the expert’s evaluation of lost revenues, the most significant pillar. The pillars we identify are not the only considerations for formulating a damage opinion but they provide a clear framework to build out a sound analysis.

When formulating an opinion of lost profits, the expert may also consider the defendant’s profits (disgorgement), mitigation, and tax impacts. These topics will not be addressed in this article.

Assumed Liability and Causation

The damage expert assumes that the legal allegations are true, and in most cases that the alleged harm caused the damage. The legal allegations and the fact of causation is most often supported by legal argument and fact testimony and remains a dispute for the judge or jury to decide. While the damage expert may not have the expertise to agree with the causation assumption, the expert should not proceed with an analysis if the expert disagrees that the allegations caused the harm. An expert’s credibility will be diminished when they provide calculations and do not believe the underlying premises for their calculations.

Lost Profits Pillar One: Lost Revenues

Lost revenues make up the most material component of a lost profits calculation. In most cases, every other component represents a fraction of lost revenues. Therefore, the damage expert and parties must expend considerable effort showing reasonable support for the calculation of lost revenues. Common mistakes include relying exclusively on an industry expert who has little experience in the rigors of litigation, or trusting the results of a theoretical projection model without offering tangible support or industry expert confirmation.

We recommend combining a three-pronged strategy to developing a well-supported opinion of lost revenues. This strategy includes structuring sound theoretical models that incorporate reliable underlying data, consulting industry expertise, and finally applying common sense to make sure the result reconciles with reality.

Sound theoretical models include methodologies established in industry guidance materials and court cases.[1] In our experience and review of guidance materials, we believe the most generally accepted methodologies to determine lost revenues include the following:

Lost Revenue Method #1: Before and After

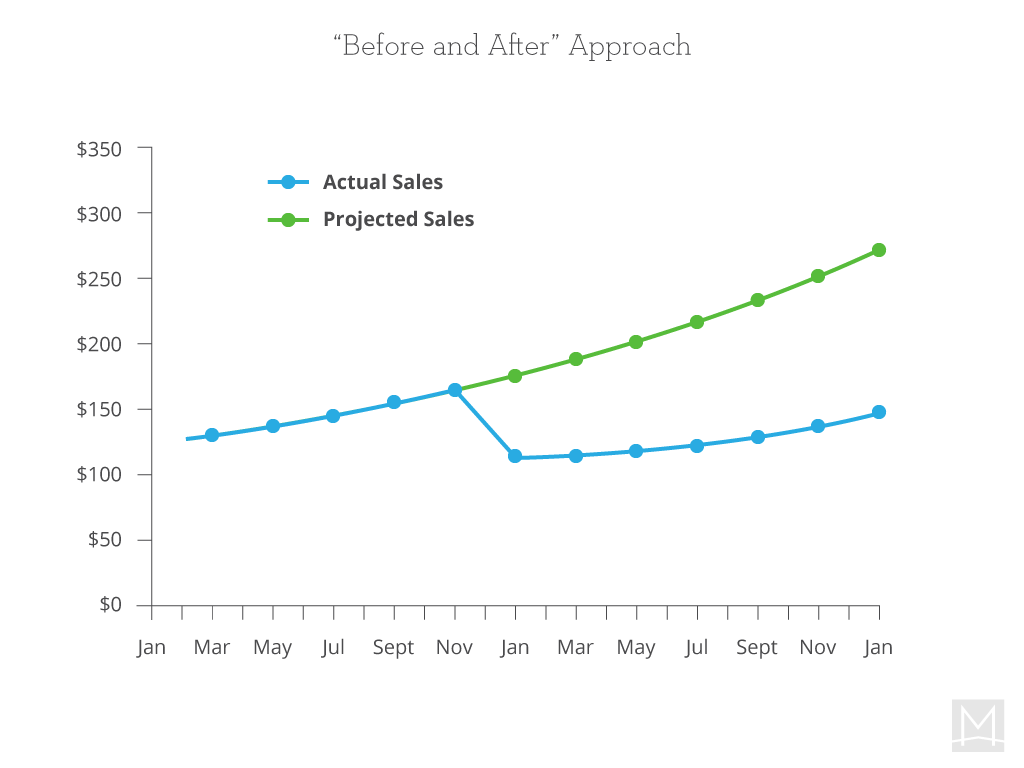

The before and after method assumes that what the plaintiff had earned in the past, they could have earned in the future, but for the alleged harmful act. This method works well when a plaintiff has a track record of earning revenue that was allegedly lost. We like to use the before and after method because when developed correctly, the result makes intuitive sense and the model generates a visually appealing graphic that demonstrates harm.

Consider an example: An apparel manufacturing company suffered from a breach of contract with one of its key distributors, resulting in a significant loss of sales. The blue line in the chart shows the actual revenue received by month. The blue line drops at the point where the distributor breached its contract. The green line shows projected revenue, but for the alleged breach. The damage expert calculated the “but for” green line by identifying historical sales levels and historical growth rates and projecting future revenues assuming continuance of the historic trend. The damage expert then determines lost revenue as the difference between the “but for” green line (expected) and the blue line (actual). The calculated amount of lost profits should be confirmed by consultation with industry information (either an expert or industry research) and application of common sense.

For this method to work, the fact pattern must contain a history of revenues prior to the alleged harm. If the plaintiff does not have a prior history of revenues, a different model should be used.

In addition, the expert must investigate the existence of other factors that could have caused revenue to decline, other than the allegations at issue.

In the example above, suppose at about the same time as the distributor’s breach of contract, a key marketing employee left the company. The departure of the marketing executive also could have contributed to a revenue decline. This extrinsic factor example shows that an expert cannot merely rely on the results of a model to project sales into the future without gathering evidence that may contradict or corroborate the results of the model.

To evaluate the impact of the extrinsic factor, the damage expert could conduct research, interview industry experts and review depositions, to understand the significance of the marketing executive’s impact on revenues.

Lost Revenue Method #2: Yardstick

The “yardstick” method to determine lost revenues looks for another product, service, or company within the industry that can reasonably be compared with the damaged company or product. The expert assumes that the damaged company would have performed as well as the yardstick, if not for the wrongful act.

An expert should consider using the yardstick method when the plaintiff does not have its own track record of revenues that they allegedly lost, but had a reasonable prospect of earning the revenues in question. The yardstick method assumes that since another company does have a track record of generating the predicted revenues, that the predicted revenues are possible and reasonable to earn, assuming no other obstacles, and that the yardstick is comparable. Both the Before and After method and the Yardstick method obtain historical sales records that show that claimed lost revenues have been earned in the past, thereby increasing an expert’s reasonable certainty that the plaintiff could have earned the revenues in the future, but for the harmful act.

An expert should also consider elements of the yardstick method when a company has a sales history, but the company expected future sales to be greater than or less than historical revenue trends, but for the alleged harm. For example, a plaintiff suffered from a breach of contract related to a product category that had become obsolete and had experienced a sudden decline in sales. Due to obsolescence, the plaintiff expected that future revenue would have been less than historical revenue, but for the breach. A yardstick method would look for a comparable company or overall industry sales decline rates to determine a reasonable basis to support the projected decline rate in revenues.

One must carefully select a reasonably comparable yardstick to use this method successfully and potentially adjust the yardstick data to account for differences between the plaintiff company and the yardstick.

Yardstick Method Example:

An athletic footwear company failed to manufacture and sell a signature line of footwear and apparel for a particular athlete. Because the signature line was never produced, the expert examined other athlete signature lines of footwear and apparel to determine the expected revenue size of the plaintiff athlete’s line. The expert believed that sales data from other athlete signature lines most closely predicted the potential performance of the plaintiff athlete’s line. However, significant challenges existed when comparing levels of popularity and perceived market image between various professional athletes. During the ensuing arbitration, debate was unending regarding the comparability of one athlete with another, because of the subjective nature of fashion and popularity.

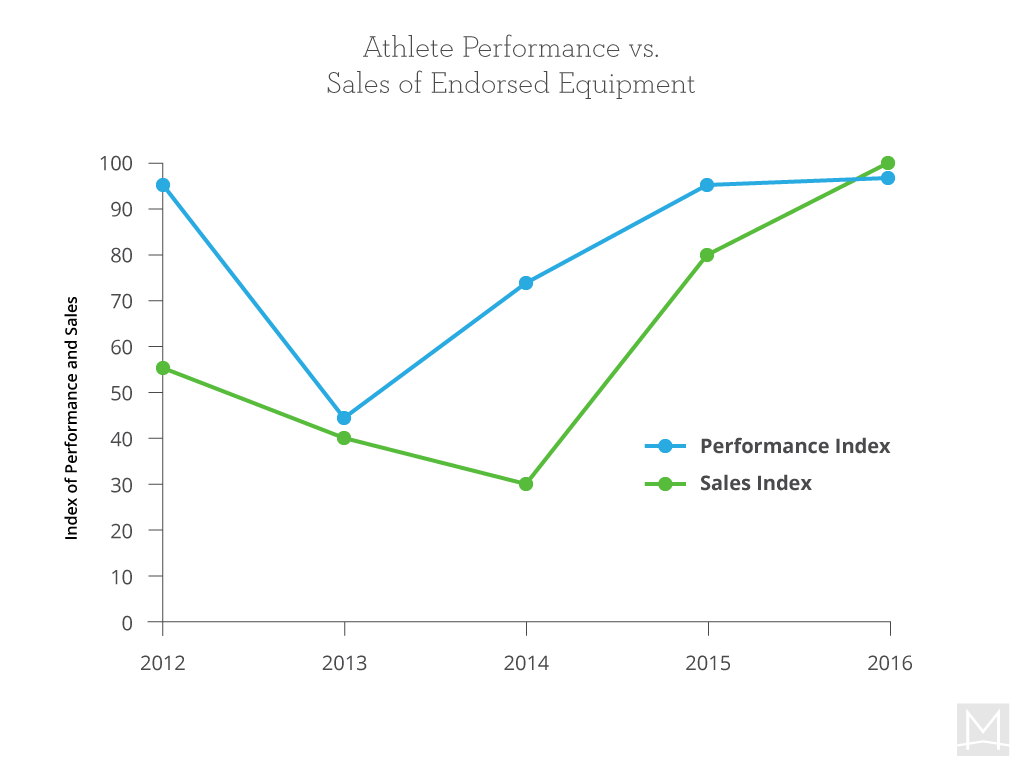

In the same case involving a footwear company’s failure to produce an athlete signature line, the expert studied the sales growth rate of sports equipment endorsed by the same athlete to determine the market impact of a temporary decline in the athlete’s performance.

The chart below shows the sales index line representing the sales trend of endorsed sports equipment. The performance index line represents a measure of the athlete’s performance. This data indicated that consumers did react, although with a delay, to changes in the athlete’s performance. The expert then applied those same sales decline and recovery rates to the expected sales of the athlete’s signature line that should have been produced during the same time period.

The greatest challenge with the yardstick method is demonstrating comparability between the damaged entity and the yardstick. The expert should consult industry expertise, such as an industry expert or specific market research that will prove that the product or service would have received market acceptance. In the athlete signature line case, the experts studied several national popularity surveys to support the assumption that the harmed athlete could have sustained a successful signature line.

Lost Revenue Method #3: Specific Contract Terms

In a small minority of our cases, we have been able to look to the specific quantitative terms of the disputed contract to calculate lost revenue. This method can only be used when the contract at issue provides specific terms that can be used to calculate expected revenue, such as the specific product, quantity, price and length of time. We rarely see contracts with adequate specificity however, possibly because such clear contracts are rarely litigated.

Lost Revenue Method #4: Statistical Forecasting—Simple or Complex Regression

Regression analysis combines data and assumptions observed from the before and after and the yardstick methods and inputs that data into a more complex predictive modeling tool. When using a regression model, the damage expert identifies key predictor data sets, such as historical product revenues before the alleged harm, product revenues of a yardstick company, or other sales predictors (such as outside temperature in the ice cream industry), and inputs those data sets into a customized regression model that will yield predicted lost revenues.

Assume, for example, after six months of contract performance, an apparel company loses a contract to produce a signature line of high end women’s jeans for a celebrity, because of a breach of contract by the celebrity. To predict what sales would have been for the remainder of the contract, the expert uses a regression model. The variables that could be considered in this regression model may include the historical sales of the jeans prior to breach, industry sales of all jeans, total sales of the company, (not including sales of the signature jeans), sales of other products endorsed by the celebrity, and even economic indicators such as consumer spending.

While regression models can consider the influence of multiple simultaneous factors, they are also difficult to explain. An expert must find a way to communicate his or her damage opinion using regression in a simple and intuitive style.

If the expert uses a regression model, the expert should take great care to demonstrate the reasons the expert chose key variables and demonstrate the predictive influence of these variables on revenues. Support for chosen data sets include testimony of fact witnesses, consultation with industry experts and industry research and calculating relevance statistics, such as R-squared.

Finally, the output of a regression model should make intuitive sense and fit the framework of the facts of the case. If the answer doesn’t appear feasible, the input data may not be correct, complete or relevant. In the end, a judge or jury will evaluate the resulting opinion on how well the opinion compares with their intuition about a case.

Conclusion

Great care should be expended by the damage expert and legal team in proving lost revenues. Each of the above methods should be used with sufficient underlying data, consultation with industry expertise and validation of the conclusion with common sense.

[1] Industry guidance on calculating lost profits include: Calculating Lost Profits, AICPA Practice Aid 06-04; Dunn, Recovery of Damages for Lost Profits, 6th Edition, (Lawpress); Weil, Frank, Hughes, Wagner, Litigation Services Handbook: The Role of the Financial Expert, 4th Edition, (Wiley); Fannon and Dunitz, The Comprehensive Guide to Economic Damages, Fourth Edition, (BVR)