Following the Money in College Sports

By Serena Morones, CPA, ASA, ABV, CFE and Paul Heidt, CPA, ASA, ABV

If you’re a college sports fan, you’ve likely felt concerned by the implosion of the Pac-12 conference that will likely devastate Oregon State University and Washington State University’s athletic program. We wondered how money drives the change, so we conducted research to follow the money in college sports, shedding light on the roles of governing bodies, athletic conferences, new name image and likeness or “NIL” programs and new litigation challenging amateurism.

Our exploration unveiled a complex financial landscape involving a myriad of entities including television networks, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), athletic conferences, schools, non-profit bowl game entities, the emerging NIL entities, and, at the narrow core, student-athletes.

To our surprise, the NCAA, the governing body for the majority of schools, relies heavily on revenue from the March Madness basketball tournament, wielding little financial influence elsewhere.

The primary financial artery in college sports has become the symbiotic relationship between athletic conferences and television networks, relationships governed by a free market economy. Over the past 4 decades since a pivotal Supreme Court decision, the revenue from television broadcast contracts has grown to financially dominate college sports, changing the entire playing field to groups of market winners and losers. This article will present a transparent view of the sprawling financial landscape.

The College Sports Revenue Generating Landscape

The world of college sports is comprised of layers of entities that each generate revenue and trickle the leftover funds down to the school and then athlete level. A student athlete serves as the ground-level revenue-generating product, competing for a college or university under NCAA rules of amateurism. The schools generate direct revenues from ticket sales, merchandise, donations and other sources. Schools are organized into athletic conferences that generate their own direct revenues from TV broadcast contracts and tournaments, then distribute money to schools. The NCAA serves as a governing body, making and monitoring rules at the school level, and generating its own direct revenue from championship tournaments, distributing the surplus to schools. Bowl games and post-season tournaments are independent entities that generate direct revenue and distribute to conferences and schools. The major television networks sit at the top of the industry wielding tremendous financial influence over college sports through their ever-growing television broadcast dollars paid to conferences, the NCAA, bowl games and schools.

How much money does college sports generate?

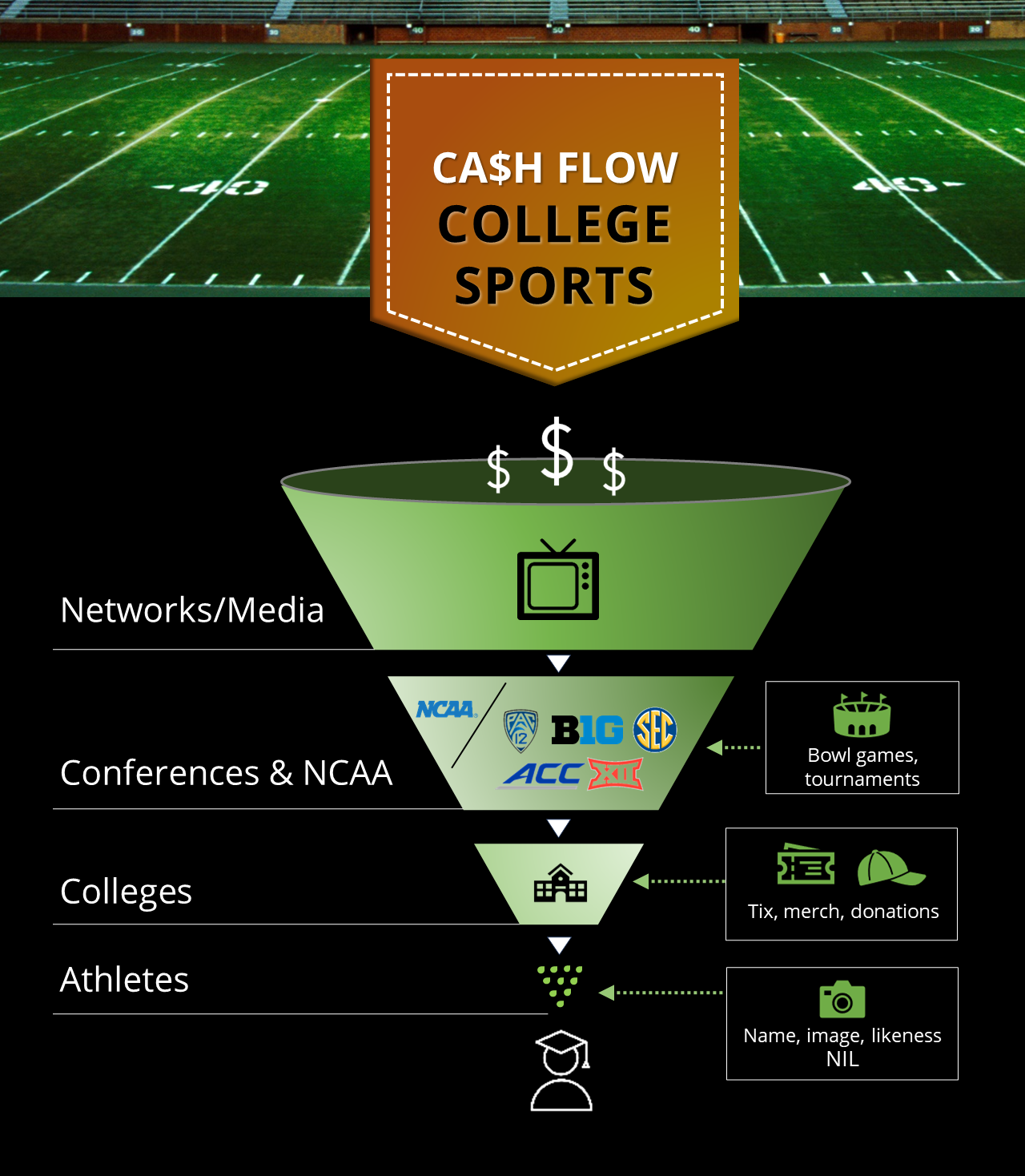

Based on data obtained through non-profit Form 990 tax returns, college athletics earned approximately $13.6 billion in total revenue in 2022 through its myriad of entities.[1] While this figure pales in comparison to an estimated $46 billion generated by the four major U.S. professional sports, individually, it outstrips Major League Baseball ($10.9 billion), the National Basketball Association ($9.9 billion), and the National Hockey League ($6 billion).

TV Broadcast Rights Dominate Revenues

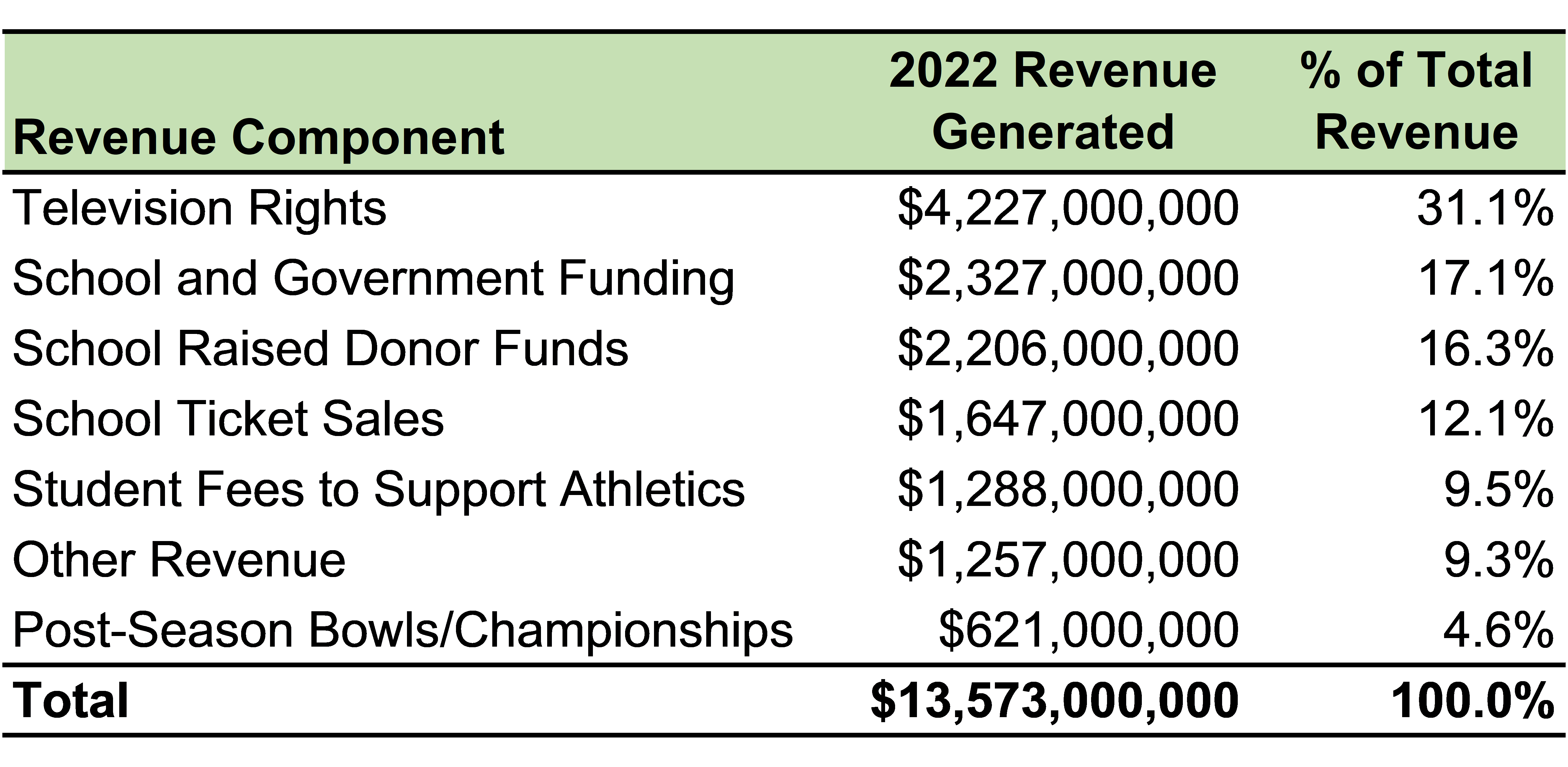

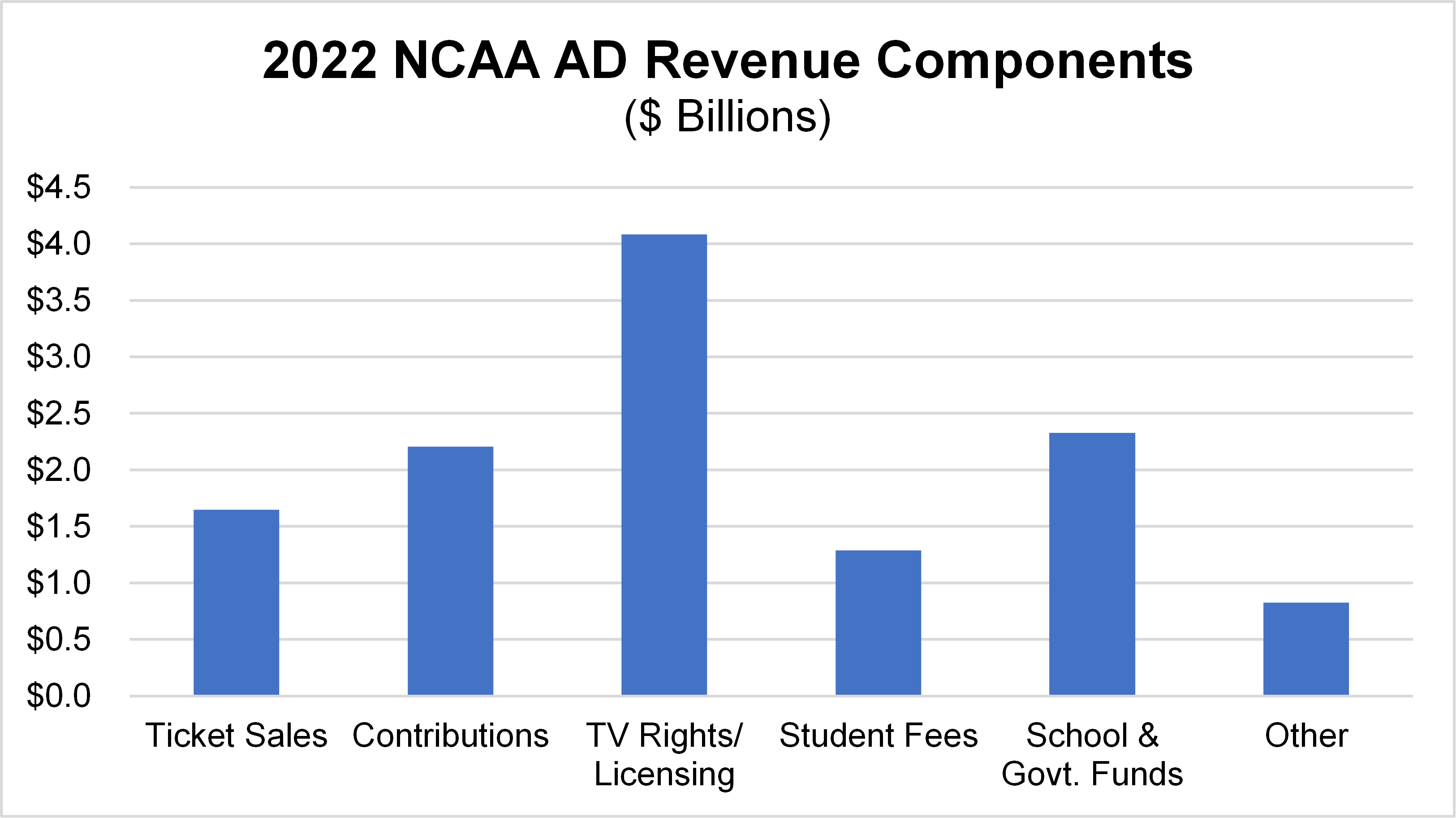

The largest single source of revenue for college sports has become television broadcast rights. In 2022, $4.2 billion[2], or approximately 31%, of revenues flowed from TV rights through all layers of the system.

The value of television dollars and the percentage of revenues it accounts for has grown significantly since the late 2000s. For example, only about 21% ($1.4 billion) of the $6.7 billion in total college sports revenue in 2009 was from TV rights.

To underscore the significance of TV revenue, roughly 77% of the NCAA’s $1.22 billion in revenues and nearly two-thirds of the Power 5 Conference (ACC, Big-10, Big-12, Pac-12, and SEC) revenues were from TV rights in 2022.

The five largest conferences, known as the Power 5 Conferences, expect renewed TV contract revenue in 2024 and 2025. The soon-to-be-negotiated television contract from the expanded College Football Playoffs is also expected to increase revenues in 2026. The impact of these new contracts is expected to increase TV revenues significantly over the next several years.[3] The rapid rise in TV dollars compared to slower-growing traditional revenues, has made TV dollars the growth differentiator for athletic programs.

NCAA’s Diminished Influence

The NCAA, a non-profit entity, regulates amateur sports competition for its 1,100 member schools in the United States, categorized into Divisions I, II and III, based on size and financial resources, with Division I including the largest athletic programs. The NCAA is governed by committees made up of volunteers from member schools who manage topics affecting sports rules, championships, health and safety, matters impacting women in athletics and opportunities for minorities.[4] Many of the NCAA rules focus on amateurism, a concept that restricts student athletes from earning compensation for participating in sports.[5]

While the NCAA regulates athlete participation in sports for its member schools, it does not control the athletic conferences, or post-season football games, and has no control over conference television contracts. In essence, the NCAA does not regulate most of the money flow of college sports.

Originally, the NCAA controlled the television deals and appearances for each school. Big football schools wanted freedom to broadcast their games on major television networks, which led to lawsuits between major college football schools and the NCAA. In June 1984, a tectonic shift in college sports occurred when the Supreme Court ruled in NCAA v. Board of Regents (of the University of Oklahoma) that the NCAA’s control of television deals represented a restraint of trade. This landmark decision ushered in a free market system for revenue generation, in lieu of an NCAA-regulated system. Subsequently, the Bowl Championship Series and the College Football Playoff (“CFP”) led to large television deals for post season competition. The Big-10 Conference formed its own television network in 2007 and most major conferences followed their lead over the next decade.[6]

The NCAA managed to retain media rights to basketball’s March Madness tournament and as a result, the majority of the NCAA’s revenues are derived from this highly popular basketball championship tournament. The NCAA generated a record $1.22 billion of revenue in 2022 and more than 93% of that came from March Madness ticket sales, merchandise and television broadcast rights. CBS and Turner Sports will pay the NCAA up to $19.6 billion over a 22-year contract term.[7] If one were to define the modern NCAA by its revenue sources, it would be described as a basketball tournament organization.

The NCAA distributes its revenues to member schools after paying its operating expenses, with $682 million going to member schools in 2022.

Athletic Conferences Exert Substantial Financial Influence

After the 1984 Supreme Court Decision, conferences stepped into the position of negotiating television rights on behalf of their member schools. Collegiate athletic conferences, non-profit organizations comprised of 8-16 member schools, are governed by boards made up of university presidents responsible for budgeting, hiring conference commissioners, enforcing rules, and admitting new schools.[8] Conference commissioners manage the day-to-day operations and hold significant sway over shaping revenue for the conferences, given that university presidents often lack experience in sports business matters.[9]

Conferences Collect Revenue and Distribute to Schools

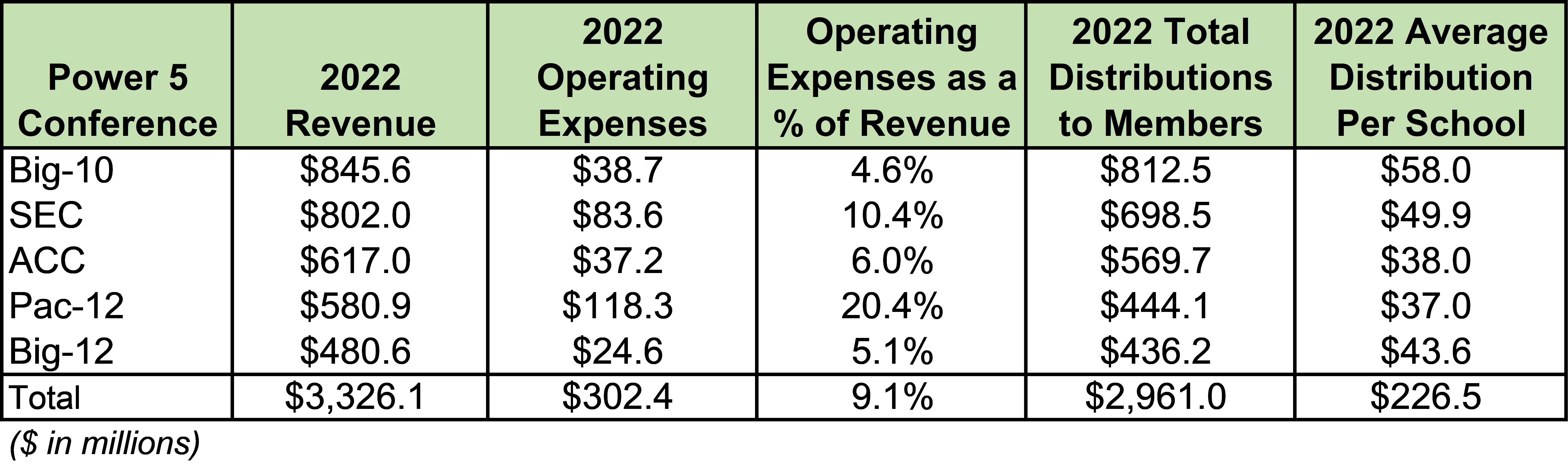

Conferences amass revenues from television contracts, sponsorship deals, and ticket sales, distributing a substantial portion to member schools. The Power 5 Conferences, the most prominent in NCAA Division I college football, gained a unique status of additional autonomy from NCAA rules in 2014.[10] The Power 5 conferences generated substantial revenue in 2022 and distributed to member schools as follows:

We note that the Pac-12 Conference’s 2022 operating expenses equaled 20.4% of revenue compared to an average of 6.7% of revenue for the other four major conferences. A key difference in spending was on salaries, compensation, and benefits, in which the Pac-12 Conference spent $36.6 million in 2022, or 6.3% of revenue, while the other four major conferences spent an average of $11.5 million, or 1.7% of revenue. This overspending by the Pac-12 Conference, which resulted in less money being distributed to the member schools, may have also contributed to the demise of the conference.

Outsized TV Deals Shape Conferences

Each Power 5 Conference secures its own television rights deals. In 2020, the SEC signed an exclusive 10-year media rights deal with ESPN that runs from 2024-2034 at an estimated total value of $3 billion. The Big-10 followed suit in 2022, entering a seven-year deal through 2030 with NBC, CBS, and Fox exceeding $7 billion.[11] This growing revenue gap between the top two earning conferences (Big-10 and SEC) and the remainder of the Power 5 Conferences has triggered new conference realignments, such as UCLA’s move to the Big-10 Conference from the Pac-12 Conference due in part to the school’s enormous losses sustained during the Covid-19 shutdown.[12]

Power 5 Conference revenue has consistently grown by 10% per year between 2013-2022 with television rights generating nearly two-thirds of that revenue in 2022. The rest of the revenue was generated from postseason bowl games (21.2%), distributions from the NCAA (8.9%), and other sources (4.2%). In 2022, the Power 5 Conferences distributed 91.0% of their revenues to member schools.[13]

Uncertain TV Deal Leads to Pac-12 Implosion

In 2022, facing expiration of its 12-year, $3 billion television rights contract in 2024, the Pac-12 Conference unsuccessfully sought a new television rights contract with ESPN and Fox but ultimately ended up with a riskier proposal from Apple TV.[14] As a result of the television revenue uncertainty and the need to address losses incurred during the Covid-19 shutdowns, UCLA and USC announced their departure from the Pac-12 conference in 2022. This event triggered a domino effect with other Pac-12 schools accepting invitations to join other conferences in 2023, except for Oregon State and Washington State who are now the lone remaining members of the Pac-12.

As a result, Oregon State’s athletic department anticipates an 84% decline in conference and media revenue, plummeting from $42.7 million in fiscal year 2024 to $6.7 million in fiscal year 2025, raising significant concerns about the future of its athletic program. Oregon State’s plight underscores the downside risk of a free-market revenue generating system in college sports.

In the 1980’s, the schools clamored for autonomy to negotiate television contracts directly, opting for freedom over NCAA regulated fairness. However, with autonomy comes risk and reduced protection, and in the case of Oregon State, the free-market autonomy led to severe funding cuts to their long-standing athletic programs, undermining their competitive opportunities.

College Football Playoff and Bowl Games Add Big Money

The college football postseason bowl games and the College Football Playoff (CFP) inject big money to the conferences and schools, as television networks have paid substantial sums for broadcast rights. The bowl game non-profit entities pay distributions to the competing teams and their respective conferences.[15]

During the 2022-2023 season, there were 43 postseason bowl games, including the three-game[16] CFP, with payouts to the conferences ranging from $225,000 for the less prestigious bowls to upwards of nearly $100 million for inclusion in the three game CFP.[17] The CFP will expand in 2024 from three games to eleven games. Early estimates value the television rights for the 11-game football tournament at $2.2 billion annually, a sharp increase from the estimated $470 million for the three-game system in 2023.[18] [19]

Schools Depend on Revenues from Conferences

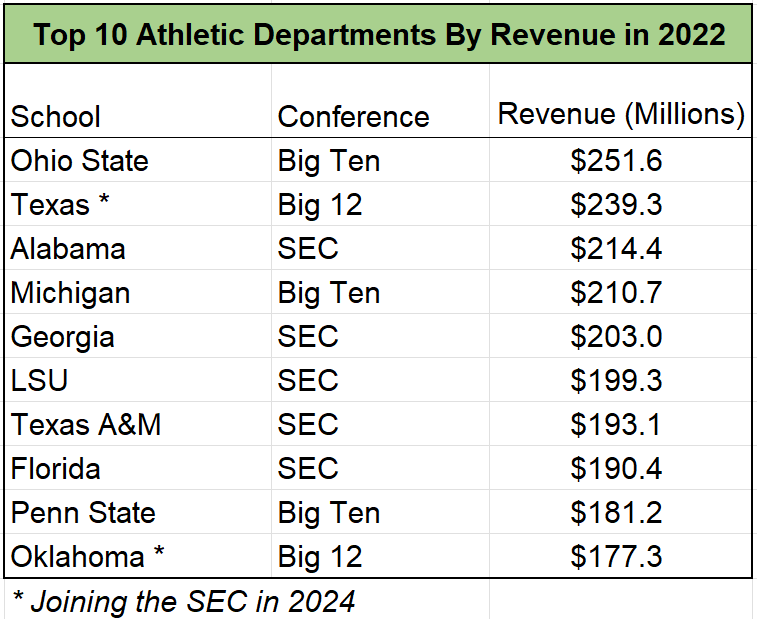

Division I public-school athletic departments (232 schools) generated $12.4 billion in revenue in 2022, with radio and television rights providing the largest revenue source, primarily distributed from conferences and the NCAA. [20]

How is College Sports Money Spent?

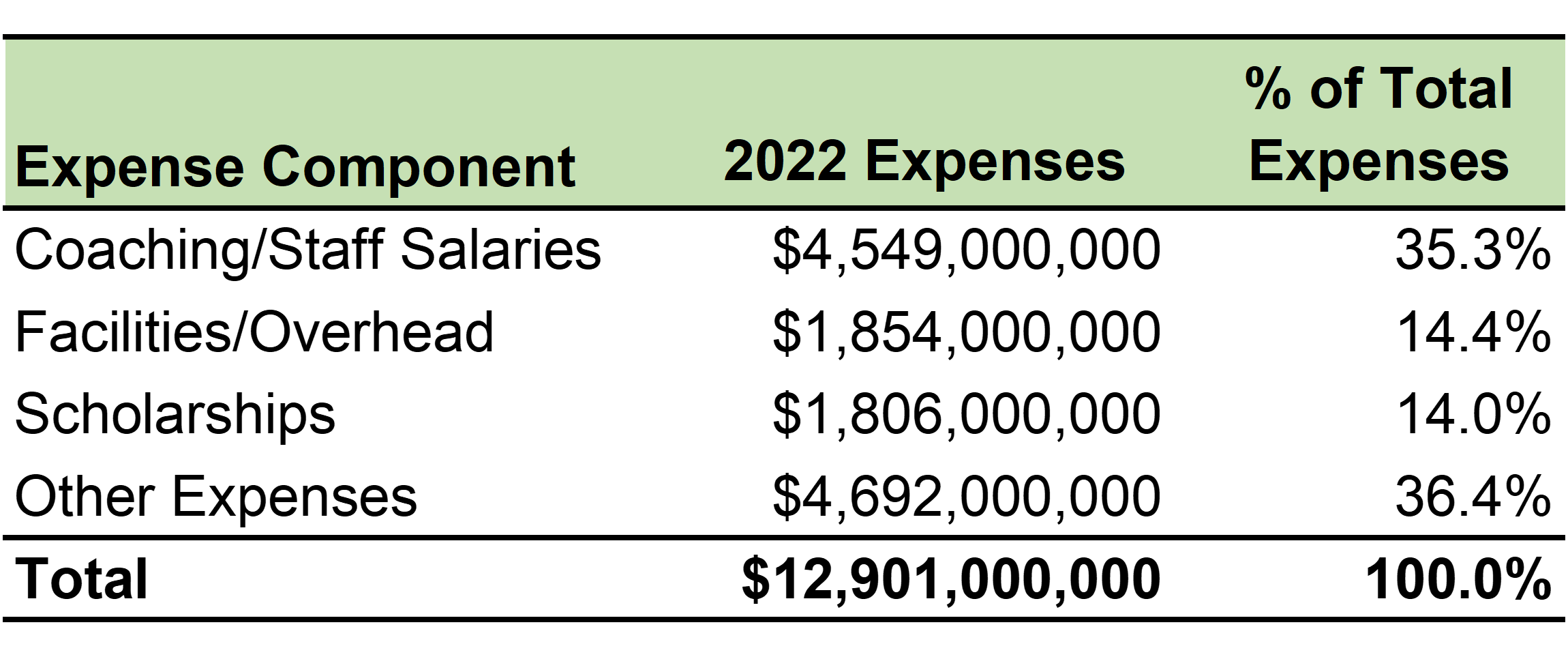

We consolidated financial data for all of the layers of entities and found that of the $13.6 billion revenue earned in 2022, the entities spent $12.9 billion. Over one-third, or approximately $4.5 billion, was spent on coaching and staff salaries, while only $1.8 billion (13.3% of total revenues) was spent on student-athlete scholarships and aid:[21]

We consolidated financial data for all of the layers of entities and found that of the $13.6 billion revenue earned in 2022, the entities spent $12.9 billion. Over one-third, or approximately $4.5 billion, was spent on coaching and staff salaries, while only $1.8 billion (13.3% of total revenues) was spent on student-athlete scholarships and aid:[21]

Schools Spend Large Sums on Coaching Salaries and Facilities

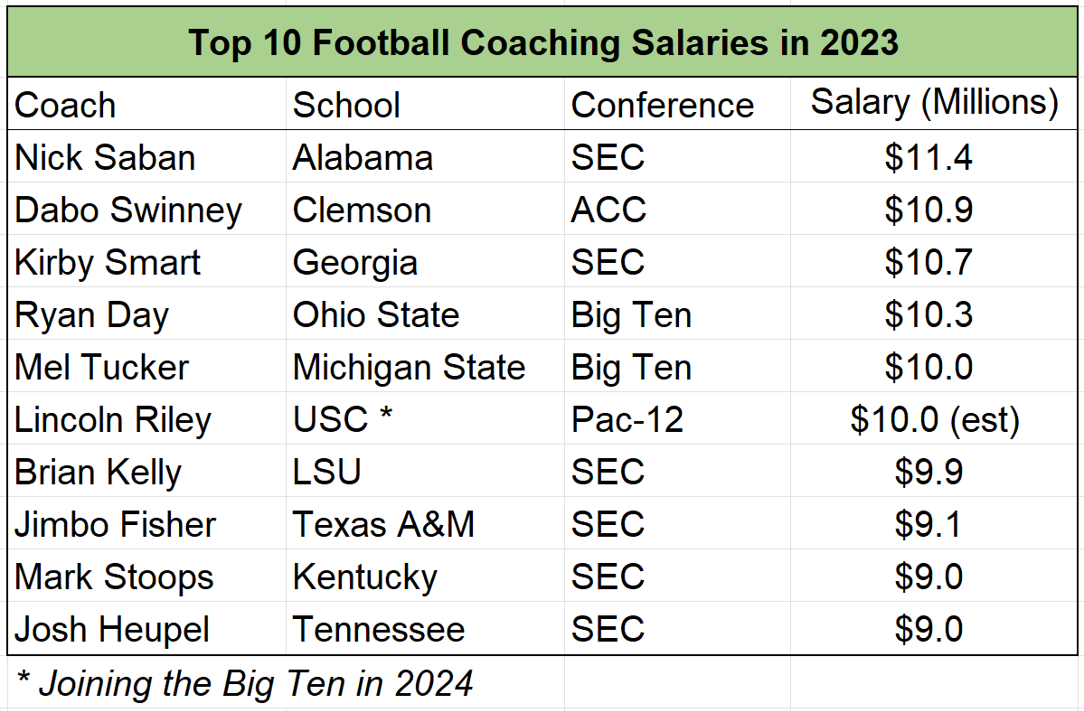

School athletic departments spent $11.9 billion in 2022, spending the most on coaching and staff salaries as a single expense category at $4.3 billion. The schools spent $1.9 billion on facilities and overhead, $1.8 billion on athletic scholarships, and $3.9 billion on all other categories of expenses. The amount schools have spent on coaching, particularly in college football, has ballooned in recent years. The highest-paid college football coach, the University of Alabama’s Nick Saban, received annual compensation of $11.4 million[22] in 2023, which is nearly one-third of what the school spent on facilities and overhead ($37.0 million) and more than half of the university’s scholarship expenses for all sports ($19.0 million).

In stark contrast to the 35% of total revenues spent on coach and staff salaries, and outsized individual coaching salaries, student athletes have historically received minimal benefit from the revenues generated from college sports due to the NCAA’s amateurism rules. According to our data, student scholarships totaled 15% of revenues in 2022. However, athletes generating television viewership, namely football and basketball athletes, receive a much smaller percentage than average because schools use profits from football and basketball to fund scholarships in other sports. One research study estimates that college football and basketball players receive benefit equal to less than 7% of revenue generated by their play.[23]

NIL (Name Image Likeness) Initiates Power Shift

A new financial dynamic called NIL has begun to disrupt power dynamics by compensating athletes, causing questions, confusion, proposed legislation and litigation.

In 2021, the NCAA responded to pressure to improve athlete benefits and introduced the concept of NIL, which allows college athletes to profit from their “name, image or likeness” – their personal brands, endorsements, and social media influence. In 2023, its second year of existence, NIL revenues are estimated to total $1.2 billion. [24]

Currently 80%[25] of NIL money is raised by “NIL collectives”. Collectives are typically non-profit entities loosely affiliated with a school. These collectives receive donations from boosters, alumni, and fans of a particular school, then pay the funds to student athletes. Corporate sponsors pay the remaining 20% of NIL money for brand endorsements. Since NIL payments go directly to athletes, the new financial opportunities can begin to bridge the vast gap between the student athletes that generate revenue at an estimated of 7% of revenues to professional athlete compensation at approximately 50% of revenues. [26]

Where do we go from here?

In our opinion, college sports have evolved into a two headed monster with one head of revenue generation at the conference/school level and the other head of amateurism at the NCAA/athlete level.

The tension between the two models appears to be on the verge of breaking, with money generation as the winner. Significant new legal challenges to amateurism, such as the College Athlete NIL Litigation, Johnson v. NCAA, and Hubbard et al v. NCAA could lead to a massive shift in the financial landscape of college sports. Furthermore, the escalating influence of the television networks’ relationships with the conferences could continue reshaping conferences, creating more pronounced winners and losers in athletic departments.

The free-market financial relationships sanctioned by the Supreme Court in NCAA v. Board of Regents, appears be inexorably propelling college sports towards a market-driven system that rewards the highest performing conferences, schools and athletes.

————————————————————-

See a shorter version of our article published in the Portland Business Journal on 11/17/2023:

Opinion: Following the money in college sports and the Pac-12 shakeup

Authors

Serena Morones, CPA, ASA, ABV, CFE

[email protected]

Paul Heidt, CPA, ASA, ABV

[email protected]

Thank you to contributing authors and researchers, Kori Bogard and Tyson Slesnick.

Kori Bogard, CPA, CFE, CFF

Tyson Slesnick, CFE, Forensic Data Analyst

—————————————————————————————————

[1] Excludes estimated NIL revenue.

[2] Includes revenue from radio and television broadcasts, internet, and e-commerce rights, as well as revenue from corporate sponsorships, licensing, sales of advertisements, trademarks, and royalties.

[3] Projected 2026 television revenue is based on new contracts negotiated for the Big Ten, SEC, and Big-12, as well as the elimination of the Pac-12 contract, while the post-season bowls/championships revenue is based on a newly negotiated contract for the CFP estimated at $2.2 billion per year.

[4] “Governance” NCAA.org.

[5] http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/AMA/compliance_forms/DI/DI%20Summary%20of%20NCAA%20Regulations.pdf

[6] “Why the NCAA doesn’t control college football and never will,” Brandon Marcello, 247 Sports, July 23, 2020.

[7] “March Madness Daily: The NCAA’s Billion-Dollar Cash Cow,” Eben Novy-Williams, Sportico, March 26, 2022.

[8] “Big Ten Council of Presidents and Chancellors, Big Ten Conference, 2023.

[9] “Meet the commanders-in-chief,” Pat Forde, ESPN, August 8, 2011, and “Madkour: The presidential predicament in college sports,” Abraham Madkour, Sports Business Journal, August 14, 2023.

[10] Section 5.3.2.1 of the NCAA Constitution grants the five conferences autonomy “to permit the use of resources to advance the legitimate educational or athletics-related needs of student-athletes and for legislative changes that will otherwise enhance student-athlete well-being”. Eleven areas of autonomy are listed, including promotional activities unrelated to athletics participation, pre-enrollment expenses and support, and financial aid.

[11] “Big Ten leads Power Five conferences with $845.6 million in revenue in 2022 fiscal year, per report,” Dean Straka, CBS Sports, May 19, 2023.

[12] “UCLA reports highest COVID-19-related financial losses out of all UC campuses,” Kaitlin Browne, Daily Bruin, October 8, 2020.

[13] Based on data derived from the ACC, Big-12, and Pac-12’s 2022 Form 990s.

[14] “Pac-12’s Apple TV deal fails to stop five more schools leaving,” Steve McCaskill, Sports Pro Media, August 7, 2023.

[15] “How much does it cost to sponsor a college football bowl game,” Eric Revell, Fox Business, December 28, 2022.

[16] In 2014, the CFP expanded from one championship game to its current format of 4 teams and 3 playoff games. The CFP is scheduled to expand to a 12-team, eleven-game playoff format for the 2024-2025 season.

[17] “College Football Playoff Payouts 2022-2023,” Business of College Sports, November 23, 2022.

[18] “Expanded CFP Could Fetch $2.2B In Annual Media Rights Fees,” Michael McCarthy and Amanda Christovich, Front Office Sports, September 6, 2022.

[19] “Playoff composition, revenue sharing, NCAA influence up for grabs as college football’s power structure shifts,” Dennis Dodd, CBS Sports, August 11, 2023.

[20] “SEC, Big Ten each top $2 billion in athletic department revenue, outpacing Power Five foes,” Steve Berkowitz, USA Today, June 14, 2023.

[21] Other expenses include guarantees paid to other schools, bowl game expenses, recruiting, team travel, equipment and uniforms, game day expenses, fundraising and marketing costs, spirit group support, medical expenses and insurance, conference dues, meals and snacks, and the value of university-provided support.

[22] “Who Is Highest-Paid Coach in College Football?,” Amanda Christovich and Doug Greenberg, Front Office Sports, October 4, 2023.

[23] https://www.nber.org/digest/202011/revenue-redistribution-big-time-college-sports

[24] “At Two: Two Years of Name, Image and Likeness in College Sports,” Opendorse.

[25] “How NIL deals and brand sponsorships are helping college athletes make money”, Business Insider.

[26] According to the 2022 Annual Report of the Green Bay Packers, players receive approx. 49% of revenues.