We’re pleased to announce our newly published article, Synergistic Values in the Organic and Natural Foods Industry, co-written by Serena Morones, Alina Niculita, and Paul Heidt in Financial Valuation and Litigation Expert, Issue 71, Feb/March 2018.

Synergistic Values in the Organic and Natural Foods Industry

Since the late 1990’s, the organic and natural foods industry has been experiencing strong consolidation by the large public food companies. Prices paid by the large food companies for smaller organic and natural foods producers reflect valuation multiples of one to five times revenue.

In this article we introduce the reader to significant developments in the organic and natural foods industry and examine two questions:

- When valuing an organic or natural foods manufacturer under the fair market value standard, should appraisers consider the transaction data in this industry?

- In the process of applying this data in the context of the transaction method, what adjustments are needed to other methods, such as the discounted cash flow method or the guideline public company method, to reconcile the indications of value from all the methods?

INDUSTRY GROWTH AND CONSOLIDATION

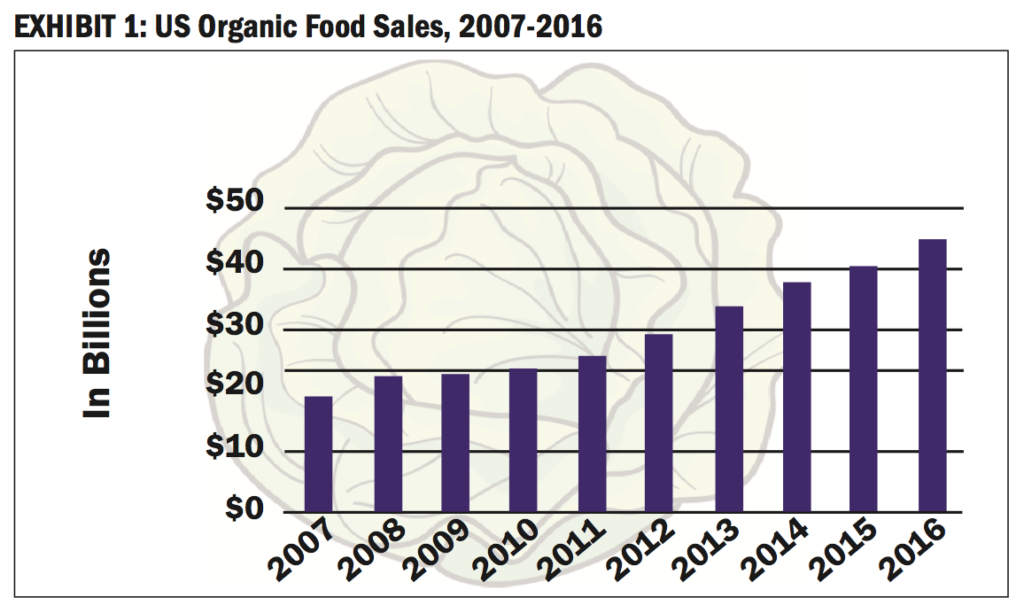

In recent years consumers have increasingly migrated towards healthy foods, including organic or natural foods. The Organic Trade Association (OTA) reports in its 2017 U.S. Organic Industry Survey that during 2016 the $43 billion in organic food sales marked the first time the American organic food market surpassed the $40-billion mark and represented more than five percent of total U.S. food sales. This was “another significant first for organic,” according to OTA.

As shown in Exhibit 1 at right, there was a 10 percent compound annual growth rate in organic food sales, from $18 billion in 2007 to $43 billion in 2016. In 2016, there was a 10 percent compound annual growth rate in organic food sales, from $18 billion in 2007 to $43 billion in 2016. In 2016, sales of organic foods in the United States increased by 8.4 percent, compared to a 0.6 percent growth rate in the overall food market.

Large food companies have not been indifferent to this trend of fast growth in consumer demand for healthy and organic foods and have gone on a shopping spree of small to medium-size organic and natural food manufacturers.

Examples of these acquisitions include WhiteWave Foods’ $600 million purchase of Earthbound Farms in December 2013 (1.1 multiple of annual revenues) and Hormel Foods’ purchase of Justin’s Nut Butters for $286 million (5.7 multiple of annual revenues) in May 2016.

The trend of high multiples paid continued in 2017 with Campbell’s Soup’s acquisition of Pacific Foods of Oregon at more than three times revenue.

UNIQUE VALUE DRIVERS

Beyond the known value drivers of earnings and expected growth, the large food companies are buying brand trust and loyalty. According to Dr. Philip Howard of Michigan State University and a scholar of the organic foods industry, one reason large multinational food companies paid a premium for smaller organic food producers was that they were eager to enter the organic market but did not have the “knowledge or relationships” to enter on their own.

Another, perhaps more important, reason was the perception that many organic food consumers do not trust the integrity of the multinational brands. For example, leading organic food retailer Whole Foods decided not to carry the organic chicken brand (Nature’s Farm) introduced by Tyson Foods, believing it was too closely associated with the large food manufacturer.1

TRANSACTION DATA

Since 2011 Morones Analytics has been collecting transaction data for acquisitions of organic and natural foods manufacturers. We obtained transaction data of at least price paid and revenue of the target for 72 acquisitions of organic and natural foods producers. We are aware of over 150 transactions of organic and natural foods product companies that took place in 2015 and 2016.²

The median price to revenue multiple for our dataset consisting of organic and natural foods manufacturers is 1.9, with several transactions having price to revenue multiples over 5.

Below, we include some observations about the buyers and sellers in the organic and natural foods industry.

Buyers

Based on our research, the pool of most likely buyers includes synergistic buyers such as:

- Large public conventional food manufacturers

- Large public organic and natural food manufacturers

- Investment funds that want to sell to the food giants

- Large private food manufacturers

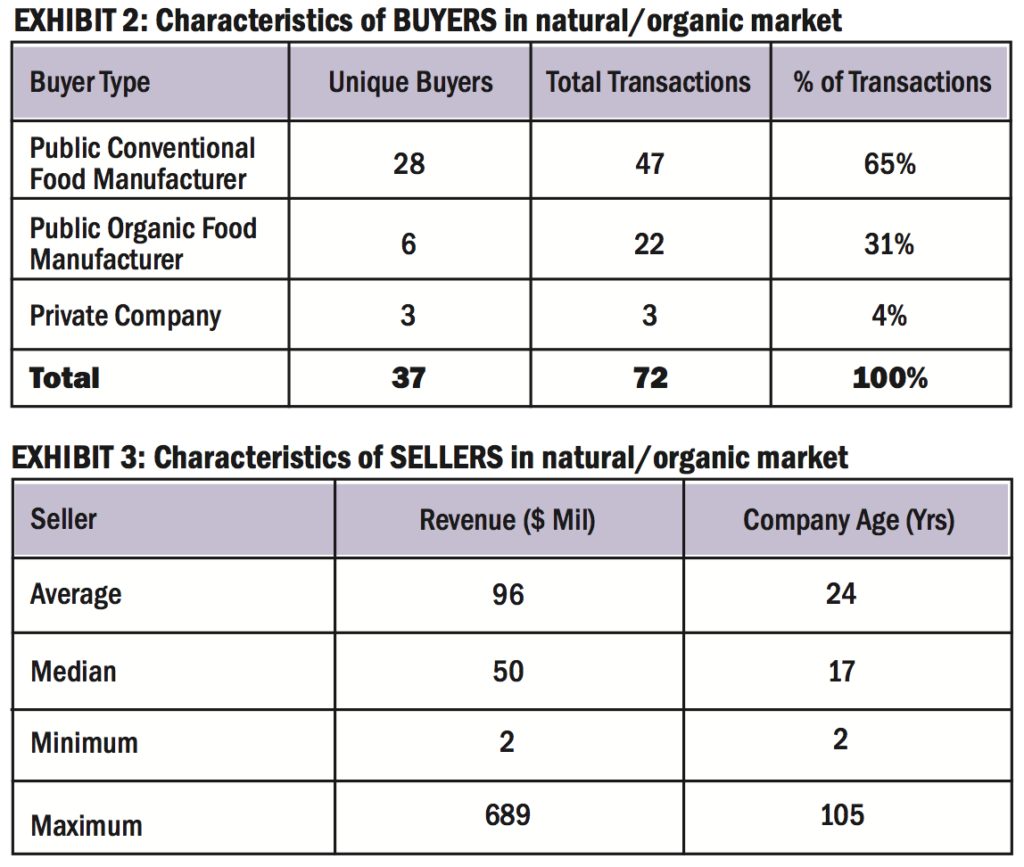

Of the 72 transactions, the buyer in almost two thirds of the transactions (65 percent) was a large public conventional food manufacturer, such as General Mills or Campbell’s Soup. Public organic food manufacturers, such as Hain Celestial and Lifeway Foods, were the buyers in nearly a third of the transactions, as shown in Exhibit 2 at right.

Of the 72 transactions, the buyer in almost two thirds of the transactions (65 percent) was a large public conventional food manufacturer, such as General Mills or Campbell’s Soup. Public organic food manufacturers, such as Hain Celestial and Lifeway Foods, were the buyers in nearly a third of the transactions, as shown in Exhibit 2 at right.

Sellers

The sellers in the organic and natural foods industry manufactured a variety of products that ranged from plant-based vegan and vegetarian food products to natural jerky and pretzels. Some of the sellers were also involved in the manufacturing of gluten-free or allergen-free breads and snacks. The sellers had a median annual revenue of $50 million and the median company age of the seller was 17 years old, as shown in Exhibit 3 at right.

APPLICABILITY OF TRANSACTION DATA UNDER FAIR MARKET VALUE STANDARD

When confronted with this transaction data, the question that needs to be answered is: Are these prices representative of the fair market value or are they simply “too high” to represent fair market value? Should we separate out these acquisitions by the food giants into a category of extraordinary and exclusively strategic, or have these acquisitions become prevalent enough to represent the hypothetical willing buyer?

In researching whether transactions by strategic buyers may be considered under the fair market value standard, we reviewed valuation literature, including case law. Pratt and Grabowski state the following: “When the universe of most likely buyers is comprised of industry players for which synergies are commonly available, the consideration of market participant synergies may be appropriate.”³

Regarding the willing buyer of controlling interests, Grabowski states:

“We have heard it said that the correct premise of value is the value of the subject business as a standalone entity. But consistent with achieving maximum economic advantage, the willing seller would investigate the marketplace for the stock of the subject business and may conclude that the market consists of a number of potential synergistic buyers. Theoreticians espouse that the synergistic buyer should not give the seller any of the benefits that the buyer expects to realize from the proposed transaction. But the reality is that synergistic buyers often give up some (and sometimes a great deal) of the synergistic value to the sellers in order to outbid other buyers.”4

Pratt and Fishman state: “In a fair market value context, by assuming reasonable knowledge and ability to negotiate at arm’s length, it is likely that if synergistic buyers are available, they will bid to reach the highest price available for the business.”5

In a tax case, the court stated that since as of the valuation date there were several potential synergistic buyers for the subject business, synergy should be considered under the fair market value standard and the business should be valued “as an entity likely to be acquired by a company with synergies,” as opposed to being valued as a standalone entity. The reason for the consideration of synergistic buyers under the fair market value standard according to the court is that: “The fair market value of property should reflect the highest and best use to which the property could be put on the date of valuation.”6

Another tax case states: “It is also our task to find the price at which a willing seller would sell. Logically, a willing seller would sell only to the willing buyer making the highest bid.”7

Valuation literature and court cases agree that fair market refers to a transacted value and that the main premise of value under the fair market value is value in exchange. As part of a valuation in the organic and natural foods industry, the appraiser should study the pool of likely buyers and the characteristics of the seller. The important question in the organic and natural foods industry is: If the pool of likely buyers includes a substantial number of synergistic buyers, as well as some financial control buyers, what type of buyer represents the hypothetical, or assumed likely buyer, for fair market value? We believe, given the right characteristics of a target, the most likely buyer in this industry would be a synergistic buyer.

APPRAISAL METHODS IN THE ORGANIC AND NATURAL FOODS INDUSTRY

Assuming we have established that the likely buyer for our subject business in the current organic/natural foods industry is a synergistic buyer, and that fair market value in this industry should account for synergies, the next step is to address how to include synergies in our valuation methods.

As we discuss each valuation method, we differentiate between value on a standalone basis and value as an acquisition target. Valuation as an acquisition target accounts for synergies that may be available in a sale to a strategic buyer.

Transaction Method

The application of the transaction method may result either in a value on a standalone basis when the buyers are pure financial buyers or in a value as an acquisition target when the buyers are strategic.8 If the target industry is undergoing consolidation and acquisitions are plentiful—indicating a pool of likely synergistic buyers—the application of the transaction method will likely result in a value of the subject business as an acquisition target and at prices that are higher than the standalone value.

As discussed above, there is a significant number of transactions in the organic and natural foods market that may be used in the application of the transaction method. However, because the only multiple that is often available is price to revenues, appraisers may be tempted to avoid using these transactions and in doing so miss quantifying price premiums in the market.9

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

DCF is a flexible valuation methodology. It can result in standalone value or value as an acquisition target, depending on the inputs used in the model. Using the subject company’s own financial projections and a cost of capital that is market-derived for the risk and size of the subject company will result in value on a standalone basis.10

On the other hand, a larger acquirer can use its own lower cost of capital to discount future income projections for the target, resulting in the value of the subject business as an acquisition target. In addition to the lower cost of capital, a potential acquirer can include synergies in the cash flow projections, also resulting in value as an acquisition target.11

In the absence of financial projections that would be representative of a synergistic buyer, what can appraisers do? One option would be to adjust the financial projections of the subject business on a standalone basis to account for potential synergies in terms of cost savings and increased revenues.

Another option may be to apply a synergistic premium to the standalone value, based on data on acquisition premiums that are sometimes used in a guideline company method,12 although in our experience that would tend to undervalue highly desirable targets in the organic and natural foods market. Another potential way to introduce the market dynamic in a DCF method could be to use a DCF with a terminal and exit multiple based on transaction data.

Guideline Public Company (GPC) Method

As part of the GPC method, appraisers commonly adjust the public multiples for differences in risk and growth between the target business and the comparable public companies under a fair market value standard.

Typically, these adjustments result in public multiples being adjusted downward, often substantially. Applying these adjusted multiples to the subject company’s fundamentals will mostly likely result in value on a standalone basis, because the appraiser has removed value enhancement realized by the larger, less risky public company. The GPC method, adjusted for size, risk, and growth, is more relevant to a valuation on a standalone basis.

To introduce synergies to the value, appraisers may model synergistic increases to the economic income to which the multiples are applied13 or apply an acquisition premium to the standalone value.14 Another way to introduce synergies to the GPC method may be to apply the unadjusted multiples of a potential synergistic buyer, basically mirroring the estimation of the discount rate in a DCF method.

BTR Dunlop Holdings

The application of each of the methods discussed above is also discussed at length in the BTR case. Below we include the court’s observations about each valuation method. The Tax Court drew a distinction between the transaction method and the guideline public company method as follows: “The principal difference between the two approaches is that comparison to publicly traded companies value [subject company] as a stand-alone company, whereas the preceding approach [transaction method] valued [subject company] as an acquisition target.”15

The Tax Court found that application of market multiples adjusted for a small-company risk and company specific risk in the context of the public guideline company method was more appropriate for a standalone valuation.

Regarding the estimation of the discount rate in the DCF method, the Tax Court found that the inclusion of a small-company risk premium and a company-specific risk premium in the discount rate were more appropriate for a standalone valuation. The court found that the petitioner’s analysis of the subject business as an acquisition target (on a synergistic basis) failed to accurately include synergies because he “did not make the necessary adjustments to the discount rate to reflect the benefits of synergies.”16

Regarding cash flow projections in the DCF method, the court found that synergistic cash flows should reflect both cost savings (increased profitability) and increased sales. The court was critical of the petitioner’s attempted analysis of the subject business on a synergistic basis because “he used the same revenue projections he used in the standalone analysis […]”17

The court commented that: “A synergistic buyer would not only achieve cost savings but would also increase sales.”18

CONCLUSION

The current strong acquisition market for the natural and organic foods industry, combined with plentiful acquisition data over more than a decade provides strong support to the proposition that appraisers should incorporate synergies into valuations of appropriate targets. Given the right characteristics of a target, we should assume that the hypothetical buyer in the natural and organic foods industry is a large public food company, likely to pay a strategic premium.

The transaction data from the acquisitions of organic and natural foods companies by the food giants should be incorporated into a guideline transaction method and given meaningful weight. Other valuation methods, including the discounted cash flow method and the guideline public company method, can be reconciled to the transaction method by incorporating synergies.

Want to learn more about our Valuation Experts? Contact Serena Morones.

To receive future articles in your inbox subscribe here.

1 Philip H. Howard, “Consolidation in the North American Organic Food Processing Sector, 1997 to 2007,” International

Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, vol. 16, issue 1 (2009), pp. 3-30.

2 “Natural and Organic Products: Q2 2017,” Capstone Partners.

3 Shannon P. Pratt and Roger J. Grabowski, Cost of Capital in Litigation, third edition (New York, NY: Wiley, 2011) p. 82.

4 Roger J. Grabowski, “Identifying Pool of Willing Buyers May Introduce Synergy to Fair Market Value,” Business Valuation Update, April 2001.

5 Jay E. Fishman, Shannon P. Pratt, and William J. Morrison, Standards of Value, second edition (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2015), pp. 50-51.

6 BTR Dunlop Holdings., et al., v. Comm., T.C. Memo 1999-377.

7 Estate of Mueller v. Commissioner, T.C. memo 1992-284, 1992 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 310.

8 Shannon P. Pratt and Alina V. Niculita, Valuing a Business, fifth edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 311.

9 The transaction method may not be appropriate in legal contexts when no sale can be presumed, such as some states’ divorce law.

10 Valuing a Business, p. 228.

11 Ibid.

12 Identifying pool of willing buyers

13 Valuing a Business, p. 267.

14 Identifying pool of willing buyers

15 BTR Dunlop Holdings., et al., v. Comm.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.